“Statelessness does not only exist in history but is ongoing, in real time and in practically every corner of the world.”

Karina Ambartsoumian-Clough, Executive Director of United Stateless

KEY MESSAGES

- Statelessness is mainly caused by one or multiple forms of discrimination. More than 75% of the world’s stateless population belong to minority groups and gender discrimination in nationality laws is another major cause of statelessness.

- Today’s world map looks very different from that of a few decades ago and political upheaval is likely to continue to bring changes to borders. When this happens, the (re)definition of who is a national of the original state and/or new state(s) can leave people stateless – a legacy that can last generations.

- Inherited statelessness is the single biggest cause of statelessness globally in any given year. Most countries require a parent to be a national, for the child to be granted nationality at birth and legal safeguards to prevent childhood statelessness are often lacking or ineffective.

- Large scale statelessness can occur where entire population groups are stripped of nationality due to discrimination on the basis of ethnicity, language or religion. Individuals can also be deprived of their nationality – a measure used to target human rights defenders and increasingly instrumentalised on the pretext of protecting national security.

- Conflicts of nationality laws, migration and forced displacement, administrative barriers and climate change can all also put people at risk of statelessness.

- The different root causes of statelessness are not mutually exclusive and someone can become stateless for a variety of reasons. Every person who is stateless or at risk of statelessness has a unique experience of the issue.

DISCRIMINATION

Racism, xenophobia and othering, as well as patriarchy, are at the root of exclusion and statelessness around the world. Discrimination against minorities (racial, ethnic, religious, linguistic etc) is a major driver of statelessness: more than 75% of the world’s stateless population belong to minority groups. Minorities may be perceived to have ties to another state and cast as ‘foreigners’, leading to denial or deprivation of nationality. Kurds in Syria in the 1960s, the black population in Mauritania in the 1980s and people of Haitian descent in the Dominican Republic in the 2000s are among the minority groups who have experienced statelessness as a result of the manipulation of nationality policy to exclude those who do not fit a certain, constructed national identity. Nationality law may also overtly discriminate against certain groups, such as in Myanmar, where citizenship is reserved to recognised ‘national races’, or in Liberia or Sierra Leone, where only those who are ‘negroes’ or ‘of negro-African descent’ may be citizens from birth. Other forms of discrimination in nationality policy can also create, perpetuate or prolong problems of statelessness. When women do not have the same right as men to transmit nationality to a child, children are at increased risk of statelessness, as the nationality of the child will then depend on the father. A stateless, absent, or unknown father, or one who cannot or does not want to take steps to confer his nationality can therefore cause statelessness. This form of gender discrimination is still present in 24 countries around the world, with around 50 countries containing other elements of discrimination against women – and sometimes men – in the change, retention or transmission of nationality. Discrimination on the grounds of disability and discrimination against rainbow families can also lead to difficulties asserting or establishing an entitlement to nationality, especially where administrative procedures do not make reasonable accommodation for such cases.

STATE SUCCESSION AND THE LEGACY OF COLONISATION

Today’s world map looks very different from that of a few decades ago and political upheaval is likely to continue to bring changes to borders and sovereignty in the years to come. When part of a state secedes and becomes independent, or when a state dissolves into multiple new states, the question emerges as to what happens to the nationality of the persons affected. The new nationality laws may conflict and leave people without any nationality, while the re-definition of who is a national of the original state (where it continues to exist) may also render people stateless. Often, it is minorities who are associated with either the successor or parent state who are deprived of nationality, exposing the discriminatory motivations for such exclusion. The ongoing legacy of colonisation has also resulted in borders being arbitrarily drawn (often dividing ethnic groups), peoples forcibly migrated (for labour) and the consequences of decades, even centuries, of colonial rule which successfully pitted different ethnic and religious groups against each other. This left its mark on nation building, the treatment of minorities and access to nationality. Statelessness has followed the dissolution of federal states into independent republics, such as in the case of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia; and state secession, such as the splitting off of Eritrea from Ethiopia and South Sudan from Sudan. Situations of emerging or contested statehood complicate this picture further, leading to unique challenges around nationality and statelessness - for instance, for the Palestinians and the Sahrawi.

INHERITANCE OF STATELESSNESS

With the exception of the Americas region, most countries require at least one parent to have nationality for the child to become a national at birth. Legal safeguards to prevent childhood statelessness are lacking in 60 countries globally and where they do exist, they are often ineffective in practice. As a result, inherited statelessness is the single biggest cause of statelessness globally in any given year (in the absence of fresh, large-scale situations stemming from one of the above problems). Situations of statelessness endure and even grow over time if states have not put any measures in place to stop statelessness being passed from parent to child – or do not implement existing measures to that effect. This means that most new cases of statelessness affect children from birth, who may never know the protection of nationality. It also means that stateless groups often suffer from intergenerational marginalisation and exclusion, which affects the social fabric of entire communities.

DEPRIVATION OF NATIONALITY

Large scale statelessness can occur where entire population groups are stripped of nationality, or denied access to nationality, due to discrimination on the basis of characteristics such as ethnicity, language or religion. For groups who have no access to another nationality, this causes statelessness. According to the laws of most states, individuals can lose or be deprived of their nationality in certain circumstances – such as when it has been acquired by fraud. Individuals may also be targeted for their political beliefs or for their activism, as has been the case, for example, in Bahrain and Nicaragua. Nationality is the gateway to political rights and its withdrawal can be a means of silencing political opponents. Human rights defenders, including journalists, have also been deprived of their nationality as one instrument used by states to shrink civil society space. Since the terror attacks of 9/11, there has also been a growing securitisation of nationality policy. In spite of security experts’ warnings that this measure is counterproductive to the fight against international terrorism, an alarming one in five countries globally have introduced or expanded the power to deprive citizens of their nationality on the grounds of disloyalty, national security or terrorism between 2000 and 2022. Europe is at the epicentre of renewed interest in citizenship stripping: 18 of the 37 countries that expanded their powers are in this region.

CONFLICT OF NATIONALITY LAWS

Each state sets its own rules for acquisition and loss of nationality, meaning that conflicting nationality laws are common. Sometimes the conflict is ‘positive’, enabling a person to acquire more than one nationality; while sometimes it is ‘negative’, leaving a person stateless. For instance, where one state confers nationality by descent (known as jus sanguinis) and another confers nationality by place of birth (known as jus soli), the combination of a particular individual’s birthplace and parentage can mean that neither nationality is acquired. Neither state necessarily have ‘bad’ laws or consider certain people as undeserving of nationality: they simply fail to qualify according to the laws of either state. This is the reason why it is so important to have safeguards in place, alongside the regular nationality rules, to prevent statelessness from arising in cases where a person would otherwise fall between the cracks. The scale of international migration today is such that conflicts of nationality laws are becoming more commonplace, increasing the need for comprehensive and effective safeguards against statelessness. One of the most important safeguards for states to include in nationality laws are to ensure that children born on the territory acquire nationality if they would otherwise be stateless.

ADMINISTRATIVE BARRIERS AND LACK OF DOCUMENTATION

Poor administration or documentation of a country’s nationals during the period of state formation or when the first citizenship registration was carried out is a surprisingly large cause of statelessness. In Thailand, Lebanon and Kuwait, for instance, statelessness became a feature of the landscape many decades – and several generations – ago, when the nationality laws were first being administered by the state. Individuals and groups who have difficulties accessing birth or other forms of civil registration may be unable to prove they have connections with the state. Without proof of place or date of birth, nor of parentage, states may dispute these facts and fail to consider a person as a national even where they would qualify under the law on the basis of these ties. The risk of statelessness is greatest for undocumented people who belong to minority or nomadic groups, migrant or refugee populations, or are affected by state succession. The Roma in countries of the former Yugoslavia and elsewhere in Europe are an evident example of where lack of documentation and civil registration can evolve into a problem of statelessness when several such factors converge. As more countries introduce digital ID systems, there are new risks of statelessness arising or becoming entrenched, where marginalised communities are left out of these systems.

MIGRATION AND FORCED DISPLACEMENT

Migration and forced displacement can be a root cause of statelessness. People may become stateless after migrating or being displaced from their country of origin. Documents can get lost or destroyed, making it difficult to (re)establish nationality. Major political changes in the country of origin can also affect migrants and refugees who are outside the country when this happens. For instance, state secession and the process of (re)determining who belongs to the new state can exclude those who have migrated or are displaced, increasing the risk of becoming stateless. Where displaced communities have lived abroad for decades, with more than one generation born in exile abroad, this can also expose them to statelessness. The nationality laws of some countries prescribe loss of nationality on the basis of a certain period of residence abroad or limit the conferral of nationality by its citizens for children born abroad, which could leave children born to migrants or refugees at risk of statelessness. Even if the law allows for access to nationality by descent for a child born abroad, it can be difficult to establish nationality in cases where the child is unable to access birth registration in the host state – for instance because the procedures are complex or inaccessible for migrant or refugee parents.

CLIMATE CHANGE

Climate change is likely to also increase the incidence of statelessness. As climate change causes more frequent and extreme weather events, more people are displaced by floods, cyclones and droughts – and people on the move are at greater risk of becoming stateless. The situation of low-lying island states also presents a particular challenge from the perspective of statelessness: what happens to the status of those whose states ‘disappear’ because the territory is no longer habitable and will large-scale statelessness ensue? There is no precedent for loss of the entire territory or exile of the entire population, and how international law would apply in such a scenario remains a subject of debate. Most experts, however, “have concluded that the “sinking island” scenario will not inevitably leave island inhabitants stateless”.

[Last updated: November 2023]

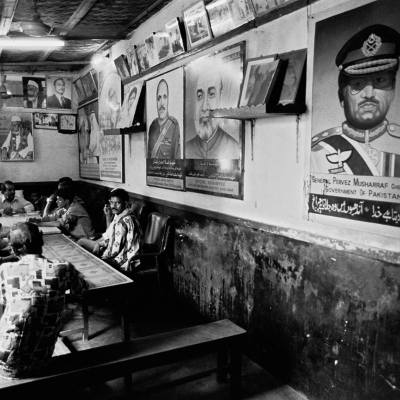

Cover image by Greg Constantine

Voices & Experiences

-

Causes of statelessness in Lebanon

![Lebanon Picture 2]()

Causes of statelessness in Lebanon

![Lebanon Picture 2]()

“When the civil war started, I had to seek refuge in Germany and couldn't register my newborn. By the time I came back, it was already too late”.

Basta

Kurdish man

Field research into the causes of statelessness in Lebanon to uncovered that one of the reasons was that some parents were unable to register register their children as a consequence of the different wars the country witnessed and their aftermath. Other parents of stateless children attributed their inability to register their children to unfortunate circumstances, such as the father’s death or illness, or the lack of official registration of their marriage at the time of their children’s birth.

-

Barriers in Accessing Nationality Documentation in Kenya

![Kenya pic 1]()

Barriers in Accessing Nationality Documentation in Kenya

![Kenya pic 1]()

“It is so unfortunate to realise that the Nubians are still facing challenges on access to nationality and citizenship. This has limited them from accessing services such as healthcare securing job opportunities or even ownership of land which is further increase if under ability both socially and economically.”

Member of Parliament Kisumu Town East,

Hon. Shakeel Shabbir

Groups working on the ground to help people navigate registration and citizenship procedures have estimated that as many as five million Kenyans face discrimination in accessing nationality documents. There is no comprehensive information on the actual number of stateless people in the country. Various minority communities are impacted, including the Galjael, Shona and those of Burundian, Congolese, Indian and Rwandan descent. Nubians and some Kenyan Somalis whose access to Kenyan identification documents is limited, also face challenges with documentation.

Voice from https://files.institutesi.org/KENYA_Together_We_Can.pdf

(page 49)

-

Gender discrimination in Bahrain’s nationality laws

![Bahrain]()

Gender discrimination in Bahrain’s nationality laws

![Bahrain]()

“My children are treated like foreigners despite living and being born in Bahrain.”

Rahima

Bahraini woman

Rahima Naser is a Bahraini woman married to a non-national and mother of three children (two daughters and one son). Her children were ineligible for university scholarships, despite graduating from high school with honours, simply because they are not considered Bahraini.

Women in Bahrain cannot pass their nationality to their child on an equal basis as men. This discrimination perpetuates the risk of statelessness and contributes to violence against women and children. While Bahraini men have the automatic right to confer nationality on their children and may confer nationality on their noncitizen spouse, Bahraini women are denied this right, resulting in wide ranging human rights violations and undermining women’s equal citizenship.

Latest Resources

-

-

Submission to the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders: “Raising their voices: human rights defenders respond to the human rights crisis”

Type of Resource: Report

Theme: General / Other

Region: Global / Other

View -

Legal Briefing on the rights of stateless Palestinians in the UK

Type of Resource: Briefing / Policy paper

Theme: Human Rights Enjoyment by Stateless People

Region: Europe

View